- Home

- John Palmer

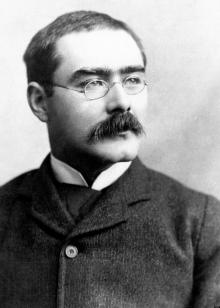

Rudyard Kipling Page 7

Rudyard Kipling Read online

Page 7

VII

THE FINER GRAIN

It has been Mr Kipling's habit all through his career to peg outliterary claims for himself as evidence of his intention later on towork them at a profit. Thus, writing _Plain Tales from the Hills_, heincludes one or two stories, such as _The Taking of Lungtungpen_ and_The Three Musketeers_, which clearly look forward to _Soldiers Three_and all the later stories in that kind. Or, again, he looks forward in_Tods' Amendment_ and _Wee Willie Winkie_ to the time when he willwrite many stories, and, in a sense, whole books concerning children._Tods' Amendment_ promises _Baa Baa Black Sheep_, and _Just SoStories_; it even promises _Stalky & Co._, which is simply the bestcollection of boisterous boy farces ever written. Then, again, thereis _In the Rukh_, out of _Many Inventions_, which looks forward to the_Jungle Book_. Finally, there is, in _The Day's Work_, clear evidenceof Mr Kipling's intention ultimately to abandon the hills and plains ofIndia and to take literary seisin of the country and chronicles ofEngland.

The first undoubted evidence that Mr Kipling, who started with skilfultales of India, was bound in the end to turn homewards for a deeperinspiration is contained in a story from _The Day's Work_. _My Sundayat Home_ is ostensibly broad farce, of the _Brugglesmith_variety--farce which might well call for a chapter to itself were itnot that broad farce is much the same whoever the writer may be. But_My Sunday at Home_ is really less important as farce than as evidenceof Mr Kipling's enthusiasm for the stillness and ancientry of theEnglish wayside. The pages of this story distil and drip with peace.Moreover, the story is neighboured with two others, all beckoning MrKipling home to Burwash in Sussex. There is the Brushwood Boy, whoafter work comes home and finds it good--good after his work is done.There is also _An Error in the Fourth Dimension_ wherein Mr Kipling isfound playing affectionately with the idea that England is quite unlikeany other country. There is in England a fourth dimension which isbeyond the perception, say, of an American railway king, who after muchamazement and wrath concludes that the English are not a modern peopleand thereafter returns to his own more reasonable land.

Of the miscellaneous stories in which Mr Kipling surrenders utterly tothis later theme perhaps the most memorable is _An Habitation Enforced_from _Actions and Reactions_. Here we are in quite another plane ofauthorship from that in which we have moved in the tales of India.There is a wide difference between _The Return of Imray_--to take oneof the most skilful tales of India--and _An Habitation Enforced_. _TheReturn of Imray_ betrays the conscious resolution of a clever man ofletters to make the most effective use of good material. But _AnHabitation Enforced_ is the spontaneous gesture of pure feeling. TheIndian stories are ingenious and well managed. Their point is made.Their workmanship is excellent. Atmospheres and impressions arecunningly arranged. But they very rarely succeed in carrying thereader as the reader is carried upon this later tide.

The feeling of _An Habitation Enforced_, as of all the English tales,is that of the traveller returned. The value of Mr Kipling's trafficsand discoveries over the seven seas is less in the record he has madeof these adventures than in their having enabled him to return toEngland with eyes sharpened by exile, with his senses alert for thatfourth dimension which does not exist for the stranger. _An HabitationEnforced_ is inspired by the nostalgia of inveterate banishment. Somepart of its perfection--it is one of the few perfect short stories inthe English tongue--is due to the perfect agreement of its form withthe passion that informs its writing. It is the story of a homingEnglishwoman, and of her restoration to the absolute earth of herforbears. In writing of this woman Mr Kipling has only had to recallhis own joyful adventure in picking up the threads of a life at oncefamiliar and mysterious, in meeting again the homely miracle of thingsthat never change. Finally England claims her utterly--her and herchildren and her American husband. It was an American who bade Cloke,man of the soil and acquired retainer of the family, bring downlarch-poles for a light bridge over the brook; but it was an Englishmanreclaimed who needs consented to Cloke's amendment:

"'But where the deuce are the larch-poles, Cloke? I told you to havethem down here ready.'

"'We'll get 'em down _if_ you, say so,' Cloke answered, with a thrustof the underlip they both knew.

"'But I did say so. What on earth have you brought that timber-tughere for? We aren't building a railway bridge. Why, in America,half-a-dozen two-by-four bits would be ample.'

"'I don't know nothin' about that,' said Cloke. 'An' I've nothin' tosay against larch--_if_ you want to make a temp'ry job of it. I ain't'ere to tell you what isn't so, sir; an' you can't say I ever comecreepin' up on you, or tryin' to lead you farther in than you setout----'

"A year ago George would have danced with impatience. Now he scraped alittle mud off his old gaiters with his spud, and waited.

"'All I say is that you can put up larch and make a temp'ry job of it;and by the time the young master's married it'll have to be done again.Now, I've brought down a couple of as sweet six-by-eight oak timbers aswe've ever drawed. You put 'em in an' it's off your mind for good an'all. T'other way--I don't say it ain't right, I'm only just sayin'what I think--but t'other way, he'll no sooner be married than we'll'ave it _all_ to do again. You've no call to regard my words, but youcan't get out of _that_.'

"'No,' said George, after a pause; 'I've been realising that for sometime. Make it oak then; we can't get out of it.'"

This story is the real beginning of Puck--to whom Mr Kipling's latestvolumes are addressed. In _Puck of Pook's Hill_ Mr Kipling takesseisin of England in all times--more particularly of that trodden nookof England about Pevensey. This book is less a book of children andfairies than an English chronicle. Dan and Una are the least living ofMr Kipling's children--they are as shadowy as the little ghost whodropped a kiss upon the palm of the visitor in the mansion of _They_.The men, too, who come and go, are shadows. It is the land whichabides and is real. We hum continually a variation of Shakespeare'ssong:

"This blessed plot, this earth, this realm, this England."

_Puck of Pook's Hill_ is a final answer to those who think of theImperial idea as loose and vast, without roots in any dear, particularsoil. _Puck of Pool's Hill_ suggests in every page that England couldnever for its lovers be too small. We would know intimately each placewhere the Roman trod, where Weland came and went, where Saxon andNorman lost themselves in a common league.

From this England, fluttered with memories and the most ancient magic,it is a natural step into the regions of pure fancy where Mr Kipling ishappiest of all. _The Children of the Zodiac_ and _The Brushwood Boy_are the earliest proofs that Mr Kipling flies most surely when he isleast impeded by a human or material document. We have here to make alast protest against a too popular fallacy concerning the tales of MrKipling. Mr Kipling's passion for the concrete, which is a passion ofall truly imaginative men, together with his keen delight in the workof the world, has caused him to be falsely regarded as a note-bookrealist of the modern type. He is assumed to be happiest when writingfrom direct experience without refinement or transmutation. We cannottrace this error to its source and expose the many fallacies itcontains without going deeper into aesthetics than is here necessary ordesirable. The simple fact that Mr Kipling's best stories are those inwhich his fancy is most free is answer enough to those who put himamong the reporters of things as they are. It sufficiently excuses usfrom the long and difficult inquiry as to whether Mr Kipling's accountof the people who live next door is accurate and minute, and allows usto assume, without starting a controversy which only a heavy volumecould determine, that, if Mr Kipling had ever set out to describe thepeople who live next door, he would have simplified them out of allrecognition. Mr Kipling has pretended, often with some success, thathis people are really to be met with in the Royal Navy or in the IndianCivil Service. But let the reader consider for a moment whom theyremember best. Is it Mowgli or is it someone who is a C.I.E.? Is itthe Elephant Child, or is it Mr Grish Chunder De? When does Mr Kip

lingmore successfully convey to us the impression that his people are aliveand real? Is it when he is supposed to be drawing men from the life,or is it when he has set free his imagination to call up the People ofthe Hills or the folk in the Jungle?

The grain of Mr Kipling's work is the finer, his vision is moreconfident and clear, the further he gets from the world immediatelyabout him. Already we have seen how happily in India he left behindhis impression of the alert tourist, his experience of the mess-roomand bazaar, to enshrine in his fairy tale of _Kim_ the faith andsimplicity of two of the children of the world--each, the old and theyoung, a child after his own fashion. _Kim_ is Mr Kipling's escapefrom the India which is traversed by the railway and served by the"Pioneer." It is the escape of Dan and Una into the Kingdom of Puck,and the escape of Mowgli into the Jungle. It is the escape, finally,of Mr Kipling's genius into the region where it most freely breathes.

We have noted that Kim is one of the Indian doors by which we enter;but there is a more open door in the first story of _The Second JungleBook_. It is the best of all Mr Kipling's stories, just as the _JungleBooks_ are the best of all his books. It concerns the Indian, PurunBhagat.

He was learned, supple, and deeply intimate in the affairs of theworld. He had shared the counsels of princes; he had been receivedwith honour in the clubs and societies of Europe. He was, to allappearances, a polite blend of all the talents of East and West. Thensuddenly Purun Bhagat disappeared. All India understood; but of allWestern people only Mr Kipling was able to follow where he walked as aholy man and a beggar into the hills. There he became St Francis ofthe Hills, living in a little shrine with the friendly creatures of thewoods, venerated and cared for by a village on the hillside.

All Mr Kipling's readers know how that story ends--how on a night ofdisaster there came together as of one blood the saint and his peopleand the wild creatures who had housed with him. It is quoted here asshowing how the old piety of India beckoned Mr Kipling into the jungleas inevitably as the old loyalty of England beckoned him into a regionwhere on a summer day we can meet without surprise a Flint Man or aCenturion of Rome.

Always the bent of Mr Kipling, in his best work, is found to be awayfrom the world. To appreciate his finer quality we must pass with himinto the Rukh, or into the country beyond Policeman Day, into themansion of lost children, or into a region where it is but a step fromthe Zodiac to fields under the plough. The tales of Mr Kipling whichwill longest survive him are not the tales where he is competentlybrutal and omniscient, but the tales where he instinctively flies fromthe necessity of giving to his vision the likeness of the modern world.

We may now realise more clearly the peril which lies in the popularfallacy concerning Mr Kipling described in the first few pages of thisbook. So far is Mr Kipling from being an author inspired and driven toclaim a share in the active life of the present, an author who unloadsupon us a store of memories and experience, that he is only able to dohis finest work as an unchecked and fantastic dreamer. The stories inwhich he imposes upon his readers the illusion that he would never havewritten books if he had stayed at home, that his stories are thecarelessly flung reminiscences of a full life--these stories arethemselves instances of the skill whereby a cunning author has beenable to conceal from his generation the deep difference betweenartifice and inspiration. A crafty author will often employ his bestphrases to describe the thing he has never really seen with the eye ofgenius. His manner will be most assured where his matter is the leastauthentic. His points will be most effectively made where there is theleast necessity to make them. Mr Kipling, writing as a soldier, ismore a soldier than any soldier who ever lived. Thereby the discerningreader will infer that Mr Kipling was not born to write as a soldier.He will know that Mr Kipling is not profoundly and instinctively anatavistic prophet, because his atavism is more atavistic than theatavism of the first man who ever was born. He will also realise thatMr Kipling writes so effectively about India because he ought to bewriting about England and Fairyland and the Jungle. He will realise,in short, that Mr Kipling is an imaginative man of letters who haswonderful visions when he stays at home, and who needs all his craft asan expert literary artificer to persuade his readers that these visionsare not seriously impaired when he ventures abroad.

Rudyard Kipling

Rudyard Kipling